Last week, we talked about how in a market crash, the best option is sometimes to be a buyer instead of a seller.

The risk-reward is much better.

But after publishing that piece, a few readers reached out to ask me, “What’s the best option to buy?”

As with anything related to options, the answer is usually, “It depends.”

However, I developed some guidelines that aim to maximize your reward relative to your risk.

Let’s talk about the strike price of an option.

The strike price is where the share transaction could occur under the options contract.

So if you buy a $50 call, you have the option to buy the stock at $50 per share, regardless of the underlying stock’s price at the time you buy.

That $50/share is the strike price.

The value of each option depends on the strike price relative to that underlying stock’s current price.

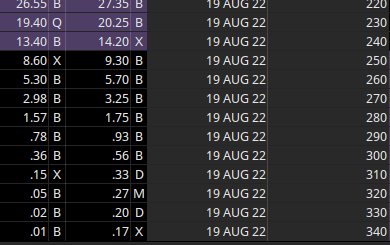

Here’s an option chain showing this:

The further “in the money” you go — meaning the underlying stock price is higher than the strike price for calls and lower for puts — the larger the option value.

And the further “out of the money” — meaning the underlying stock price is lower than the strike price for calls and higher for puts — the smaller the value.

Many option gurus out there will tell you to be “safe” and select in-the-money or slightly out-of-the-money options.

That strategy can work but has some drawbacks.

First: The options are much more expensive. Therefore, you lose some of the leverage you can get playing the options market.

Second: If the market moves hard against you, your option contracts will lose a ton of absolute value.

That means you’ll need to downsize your trades.

Third: If you’re right, and your option goes very deep in the money, the bid/ask spread widens further and leads to liquidity issues.

What about “out of the money” options?

I’m sure you’ve heard people tell you most options expire worthless.

That’s hilariously misleading.

It’s a misinterpretation of a Chicago Board Options Exchange stat showing that 10% of options contracts are exercised…

That stat actually says 10% of options contracts are exercised — meaning the options holder bought or sold the underlying shares according to the options contract.

That doesn’t necessarily mean the other 90% expire worthless. That same CBOE report said 55%-60% of contracts are closed prior to expiration.

That leaves 30-35% to expire worthless.

More recent data from the Options Industry Council found 72% are closed out before expiration, 6% are exercised… and only 22% expire worthless.

Regardless, both stats show the majority of options contracts are closed before expiration.

Think about it:

The vast majority of options traders don’t want their options to expire in the money, so they close those winning options out before expiration.

This allows them to take profits on their trade… which is the whole point of trading options.

Now, here’s the dirty secret in the options game… it’s a little advanced.

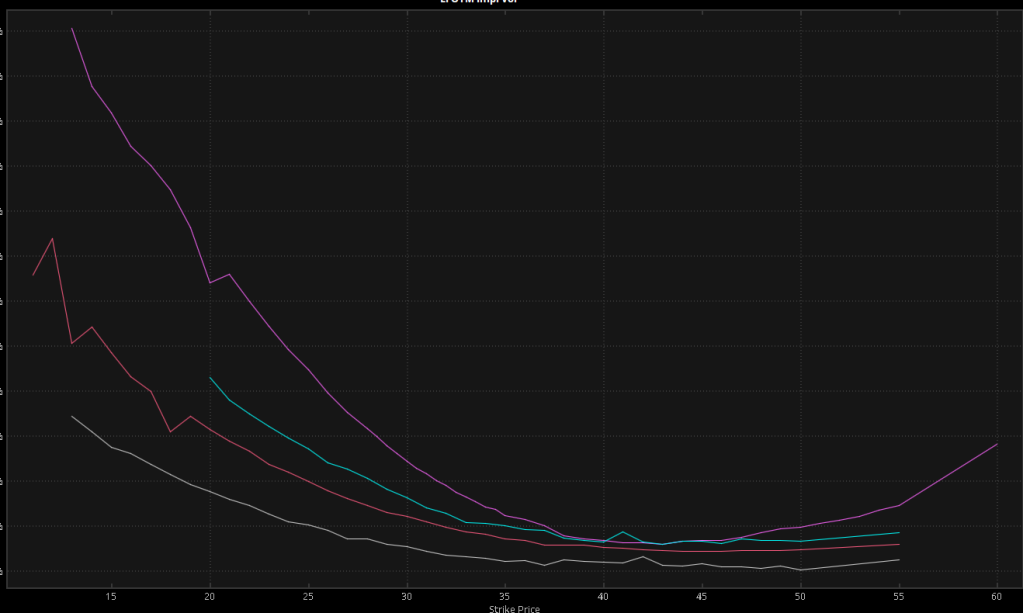

Take a look at this chart:

This shows us the options market’s implied volatility.

Each line represents an options expiration, and the strike price is on the lower end.

It’s called a “skew” chart and shows you the demand for individual options against each other.

At the time of writing, the stock here was trading at $37.

See how the IV continues to drop the higher the strikes go?

That’s because you’ll have net call sellers in a normal options market.

Investors will want to generate income and reduce their risk by selling calls, keeping the cost of the option down.

It’s also the best place to generate upside convexity.

At Precision Volume Alerts, many of our trades focus on using out-of-the-money options — around 20-30 delta — because they generate the best reward relative to our risk.

Thanks to our Trading Roadmap, we know the best place to scale out of our trade to avoid holding them to expiration.

It’s been quite a profitable system…

Go here to learn more about our Trading Roadmap (and how we use it to play options).

Original Post Can be Found Here